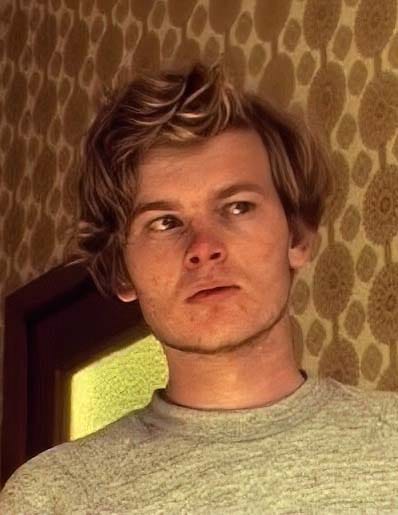

Shane Burridge

He is the man behind the film adaptation Quitters Inc.

SKSM: Tell us about yourself, and what do you do or have done.

Shane Burridge: About the only thing relevant to this site would be lecturing Film Studies at university in Beijing, otherwise it’s a mixed bag of people, places, and things not connected to movie-making in any way.

SKSM: How did you decide that shooting movies was your mission?

Shane Burridge: I was obsessively writing comics from age 10, so some years later 8mm ‘moving pictures’ were an obvious step up, since comics are basically storyboards.

SKSM: Quitters Inc. What is it in the story that you liked so much to develop into a short?

Shane Burridge: It was the only one in the book that was doable on a budget of zero. It was also the first story collection, i.e. Night Shift, that King had published at that stage, so it wasn’t like you could cherry-pick from dozens of titles. I didn’t think about that particular story at the time because I figured that no-one would take it seriously, at least not enough to find it scary. A year later the stupidly obvious thought occurred to me that I didn’t have to play it as horror at all and I could just have fun with it.

SKSM: Why did you choose Quitters Inc and not, for example, another story?

Shane Burridge: It wasn’t supposed to be a standalone thing. I was tooling about with an hour long omnibus, because I always liked the Amicus horror anthologies as a kid, and Quitters became the middle story. In that original format it didn’t have any credits before or afterwards, so when I decided to share that segment with some film enthusiasts many years later I digitally tacked on some basic titles at the start and end of the video file, using the same font as the original 8mm copy. That’s the version that has found its way onto your website.

SKSM: Can you tell me a little about the production?

Shane Burridge: It follows the basic beats of the story, but I don’t think there could have been more than a couple of lines of dialogue that were used from the original, and we did it in an off-the-cuff way more suited to our natural way of talking and non-acting ability. I can’t remember if we even used the same character names.

SKSM: What did you think of the actual film adaptation?

Shane Burridge: Cat’s Eye came out soon after I’d finished and I saw that they’d gone the same route as I had, taking it less seriously. When I went to see it I had no idea Quitters was in it. It had a cat on the poster! That was enough for me.

SKSM: Was everything planned ahead or did some things change during filming, e.g. being cut out? Were there unexpected moments or difficulties?

Shane Burridge: I had a top of the line camera, a beautiful Canon 1014XL-S, but even that couldn’t save us from technical hassles. The film fluttered in the gate on our first day (a dialogue scene in a horrendously underlit airport – even though I had a low light shutter, it still came out like a freakin’ cocktail lounge) and when I got it back from processing some weeks later I saw half of it was out of focus. Ironically one shot was supposed to have the background out of focus anyway.

Went back to the airport to do pickup shots and on the way the car caught fire. Ended up filming half the airport dialogue in someone’s basement. And that was just the start. Lens problems. Audio problems. Rabbit not co-operating. Lead character, who had quit cigarettes in real life, got back into the habit after I’d made him smoke a few, making me answerable to his girlfriend at the time. After we finished the last thing that needed to be filmed – a dialogue scene in an office – I found that the microphone had cut out for half the roll. So back we went to redo it, but in the interim the lead, naively assuming that everything was over and done with, had cut his hair drastically short. Everything had to be framed strangely, overexposed against windows, or shot through a wide-angle lens to disguise the fact that he looked different.

SKSM: What do you think of the end result of the film?

Shane Burridge: I ended up throwing out five minutes of the story because all the continuity and technical screwups got to the point where I was piecing together and looping individual words of dialogue from the out-takes bin. My edit list had weird things like “removed seven instances of tongue-clicking during dialogue” written on it. The advantage of watching it again now after a distance of many years, is that most of the seams aren’t noticeable anymore and it’s actually coherent.

SKSM: What was it like to use film in the 80s? Can you tell us more about it?

Shane Burridge: Since photochemical has now pretty much become the Stone Age of home video, people are completely oblivious of what a trial it was to use 8mm, not to mention expensive. Kodak stereo sound-striped reversal stock cost over $12 a minute, and you couldn’t just ‘rewind’ and do it over if there were any mistakes. You couldn’t even see what you’d filmed until weeks later. When the roll was finished you’d take it to a chemist, they would send it to a lab, they would develop it and post it back to you, all of this being a process about as slow as a wet chook. Also, in 8mm the sound stripe runs ahead of the acetate by 18 frames, so if you’re filming dialogue, you’re going to lose one second every time you make a physical cut in the film, which can make it look stilted when people are talking. And there’s also camera noise to deal with.You can always try dubbing it later, but that looks lousy.

What really hurts while watching these films now, though, is the image loss, because you’re seeing them digitally converted, not projected on a screen. Even though a frame of 8mm is only about as big as your little fingernail, you can get some gorgeous photography out of it if you have a good camera and you have some awareness of light. But when it’s transferred to digital, whites get blown out, blacks become grey masses, reds bleed, all the subtlety is lost.

SKSM: What do you think about the existence of a Dollar Baby and/-or short film community?

Shane Burridge: I didn’t find out about the Dollar Baby setup until sometime in the late 90s, and I remember thinking that other people around the world would have been making their own short films but that I’d never get to see any. 30 years later I find that they’re curated on this site.

SKSM: Are you a Stephen King fan? Which are your favorite works and adaptations?

Shane Burridge: King was taking off in a big way when I was a teenager because of the hit film adaptations of Carrie in 1976 and The Shining in 1980. After that, the floodgates opened and the early 80s became “This month’s Stephen King film”, so his presence back then was a big part of pop culture, which is why my attraction to his work remains in the first “half” of his career. As for my favourite book, the one I keep coming back to is Danse Macabre. I know it sounds like an unusual choice because it’s not a novel, but I like the approachable, anecdotal way he looks at ideas, which in other hands would come across as pretentious and academic.

SKSM: Is there a possibility that we will soon be able to admire your movies on YouTube or Vimeo?

Shane Burridge: That’s not even up to me anymore. About 15 years ago I’d had my prints scanned and shared a couple of them in a private site online for Halloween as a lark: “Hey guys, check out this 8mm stuff I made in the 80s”. A decade afterwards I found out that I’d somehow – I would say fraudulently – ended up on the IMDB and then some years after that, appeared here on this site, which bewilders me. It’s like that quote about The Stunt Man, “this film wasn’t released, it escaped.”.

Similarly, I wrote hundreds of articles and reviews for the IMBD starting back in 1995, when it was only a few years old and known as the Cardiff Movie Database, which have since become long-lost to time, and that somehow, like messages in bottles, have randomly surfaced again quoted in all sorts of places – websites, books, film festival programs, and (in what must be the most dubious endorsement) the director commentary for I Spit on Your Grave. I don’t know how any of it manages to keep circulating 20-30 years later, but the internet finds a way. So, like I said, nothing to do with me. As far as I know, the only site that’s still around today and has kept some of my articles is Film Threat.

SKSM: Before you adapted Quitters, Inc. you made Richard Matheson’s ‘Prey’ in 1983. Can you tell us more about that?

Shane Burridge: Another one that I can’t believe has turned up out of the ether decades later. God knows how that wound up on the IMDB. Matheson is my favourite writer – economical and with an ear for dialogue – who I’d discovered in a ‘Suspense Stories’ collection. As soon as I’d read it, I thought, wow, this could be made into a tight little film. It wasn’t until after I’d done it that I found out that it’d already been part of a TV-movie, Trilogy of Terror, which was a hundred times better because, you know, they had money.

SKSM: Where does the name “Badgefilms” come from?

Shane Burridge: Badge was a high school nickname, a diminution of ‘Burridge’, and also because I wore a badge on my school uniform which the teachers turned a blind eye to, even though it was disallowed.

SKSM: What are you working on nowadays?

Shane Burridge: Nothing filmwise. The attraction of movie-making for me had been handling actual film, holding it up to the light and looking at all the frames, cutting it and re-assembling it. It was more of a challenge, like this fragile plastic stuff was daring you to try to chop it up into a halfway decent looking end product that made sense. But as soon as home video and half-inch tape came along in the early 80s, everybody was recording (I refuse to say “filming”) their own backyard movies, which looked bloody awful.

I have very clear memories of the first time I saw an amateur movie on video: it looked like electric vomit. Good name for a punk band now I think of it. I also thought “Huh! This will never replace 8mm”. Well I backed the wrong horse there. Within the next decade you couldn’t even buy film, let alone find anywhere in NZ that would process it, so that was the end of the era for me. The thing that really crushed me was that I never got the chance to film anything in black and white, which had already become a dead duck by the time I’d gotten interested in it.

SKSM: Thank you for taking the time for the interview. Would you like to say something to those reading?

Shane Burridge: For any of you diehard King fans that made it to the end of this ramble, did you get the reference to his short stories I put in the first paragraph? Or are you going look again, suddenly notice it, and smack yourself upside the head?